Integrating Career Development within the Primary School Curriculum

08/01/20

Greg Souvan is an experienced Guidance Officer with Education Queensland. He is a Doctoral Candidate at the University of Southern Queensland focussing on 'School teacher self-efficacy for career development learning and teaching'. He recently presented at the 2019 CDAA National Conference in Canberra.

I had the pleasure of presenting a Case Study at the recent CDAA National Conference in Canberra. In my presentation, I showcased an example of how career development was being integrated into the year six curriculum in a country Queensland primary school. This program was experimenting with a pedagogical answer to the question: What does career education look like in a primary school environment? More specifically, how effectively can career education be integrated along with Queensland’s curriculum.

Career development learning in primary schools is the new frontline of preparing students for the world-of-work. However, there is very little evidence of career education being deliberately included into curriculum content in a primary school environment Australia wide. Currently, contemporary schools focus on supporting students from three perspectives, including:

- an effective whole-school Social Emotional Learning program (SEL),

- Positive Behaviour for Learning (PBL)

- and a whole school pedagogical framework e.g., ASOT (Marzano, 2007).

In my conference presentation, I explained in a post-contemporary school there is a fourth element that is critical to supporting students: the World of Work. Without career development theory, pedagogical practices in career education will be a matter of hit and miss. These theories include:

- Donald Super’s Lifespan Lifespace career development theory: a developmentally based framework towards the notion that school-aged children need to be exposed to intentional career education at all year levels of schooling (Super, 1980, 1990, 1992).

- Gottredson’s theory of Circumscription, Compromise and Self-Creation (Gottfredson, 1981, 2005): a theory that provides further insight into the how school aged children rationalise gender related job roles and how socioeconomic status may influence career decision making.

- Cognitive Career Theory (Lent, Brown, & Hackett, 1994): a theory that vocational interests are influenced by the sources of self-efficacy beliefs, outcome expectations and personal goals. These three sources from the general social cognitive theory (Bandura, 1994) are the building blocks of career development (Lent, Brown, & Hackett, 2002).

With an agenda of a theory-based ideology, we can be confident that schools are in the ideal position to provide career education learning at all age levels. School children at times do have to confront stereotyped gender roles and do need to be supported to reduce the barriers of hereditary or biological factors that may influence their vocational choices. From a social justice perspective, effective career development programs at a whole school level can have a positive impact on how children view their future selves.

The case study:

Getting teachers thinking about career education and the possibilities of how to embed it within the curriculum required a gentle approach. Primary schools are a very busy place and teachers are already juggling many priorities. I was fortunate to lead professional development activities in SEL and PBL and I used these opportunities over the past two years to sneak in world-of-work concepts into those sessions. It did not take too long before a few teachers indicated their interest and it was here that I was able to specifically work with a year 5-6 teacher to integrate career education within their curriculum.

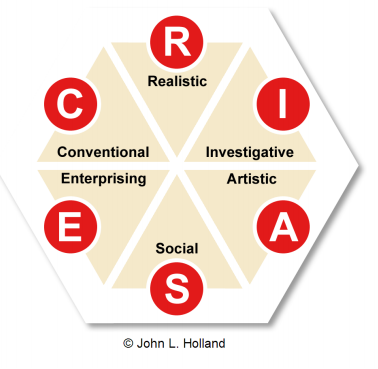

Meanwhile, I was being heavily influenced by the El Cajon Valley School District in San Diego and the amazing work that Ed Hidalgo and his team were doing in the primary classroom (Hidalgo, 2017). I was particularly intrigued about how they were using John L Holland’s RIASEC topology (Holland, 1997) in all year levels starting at kinder age children.

At the CDAA conference, I showcased how a unit from the curriculums’s Design and Technologies learning area was chosen to integrate with career education pedagogy. Students were required to work in pairs to display the process of investigating, generating and producing a project. This was ideal for an integrated approach with career development as I could see connections with RIASEC as a basis and aspects of the school’s whole school social-emotional program (PATHS). The year six project required students to work in pairs to create an arcade game made predominately of cardboard (see figure 1).

Figure 1. Year 6 assessment project - Cardboard Arcade Game. The wheel of Chocolates

In the classroom, I facilitated two lessons previously where students were introduced to RIASEC and had the opportunity to explore their codes. We discussed the project of the Cardboard Arcade games and the skills they thought they needed to be successful in its completion. We also discussed what they thought were their strengths and what skills they may need to develop, referring back to RIASEC to stimulate thoughts. This produced a great amount of excitement in their responses. After the students had built their project, we reviewed what had occurred with their projects and what they discovered about themselves. Meanwhile, I introduced the Career Bullseyes to the students to think about what education levels they may need in their future careers.

At the conference, I presented one student’s written component of the assessment and discussed how the student was able to identify her interests and abilities for which she felt she was best suited. This student was able to identify job types that were of interest to her, including the qualifications she needed. It was pleasing to see the students engaging with career activities and pondering their future possibilities.

I found that career development related activities can be integrated within the primary school curriculum. I was fortunate to work in a school that had a progressive principal who could see the value in career development in primary school. I found that teachers were receptive to experiment with career education pedagogy and that teachers demonstrated a high level of self-efficacy for career development teaching and learning. The only real barrier was time. Career development in Queensland primary schools is not a priority and each of us experimenting with the pedagogy already have competing priorities to manage. However, there are those of us willing to ensure that our students are on the cutting edge of being prepared for effective decision making ready for the world-of-work.

References

Bandura, A. (1994). Self-Efficacy. In V. S. Ramachaudran (Ed.), Encyclopedia of human behavior (Vol. 4, pp. 71-81): New York Academic Press.

Education Queensland. (2014). P - 12 curriculum, assessment and reporting framework. Retrieved from https://education.qld.gov.au/curriculum/school-curriculum/p-12

Gottfredson, L. S. (1981). Circumscription and compromise: A developmental theory of occupational aspirations. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 28(6), 545. doi:10.1037/0022-0167.28.6.545

Gottfredson, L. S. (2005). Using Gottfredson’s theory of circumscription and compromise in career guidance and counseling. In S. D. Brown & R. W. Lent (Eds.), Career development and counseling: Putting theory and research to work (pp. 71-100). New York: Wiley.

Hidalgo, E. (2017). Students Connect Their Learning. Businesses Connect Their Work. What the WoW Framework Means for 17,000 Students. . Retrieved from https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/students-connect-learning-businesses-work-what-wow-means-ed-hidalgo/

Holland, J. L. (1997). Making vocational choices: A theory of vocational personalities and work environments: Psychological Assessment Resources.

Lent, R. W., Brown, S. D., & Hackett, G. (1994). Toward a unifying social cognitive theory of career and academic interest, choice, and performance. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 45(1), 79-122. doi:10.1006/jvbe.1994.1027

Lent, R. W., Brown, S. D., & Hackett, G. (2002). Social cognitive career theory. In D. Brown (Ed.), Career choice and development (Vol. 4, pp. 255-311).

Marzano, R. J. (2007). The art and science of teaching a comprehensive framework for effective instruction. Retrieved from http://ezproxy.usq.edu.au/login?url=http://www.USQ.eblib.com.au/EBLWeb/patron?target=patron&extendedid=P_314281_0

Ministerial Council for Education Early Childhood Development and Youth Affairs. (2010). The Australian Blueprint for Career Development. prepared by Miles Morgan Australia, Commonwealth of Australia, Canberra. Retrieved from www.blueprint.edu.au.

Super, D. E. (1980). A life-span, life-space approach to career development. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 16, 282-298. doi:10.1016/0001-8791(80)90056-1

Super, D. E. (1990). A life-span, life-space approach to career development. In D. Brown & L. Brooks (Eds.), Career choice and development (pp. 167-261). San Fransisco: Jossey-Bass.

Super, D. E. (1992). Toward a comprehensive theory of career development. In D. H. Montross & C. J. Shinkman (Eds.), Career development: Theory and practice (pp. 35-64). Springfield, IL: Charles C Thomas Publisher.